BACK

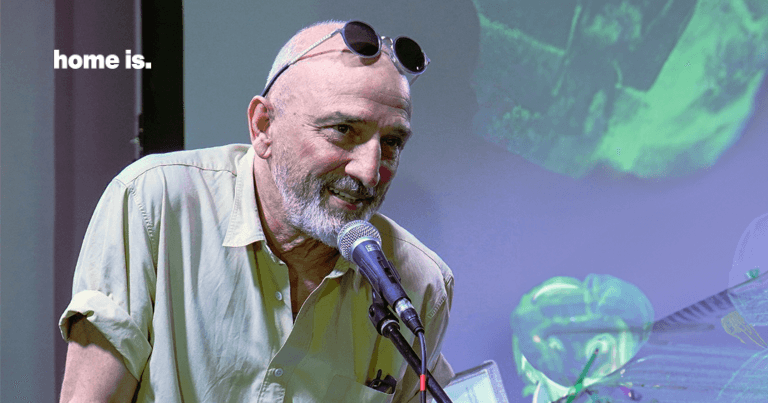

An Interview with Merab Gujejiani

2023-09-15

In today’s article, we discuss the work of architect Merab Gujejiani, who has a diverse and fascinating experience in the field. His contribution to the restoration and reconstruction of cultural heritage and historical sites is particularly noteworthy. Today, he shares insights with Homeis.ge readers about his completed projects and various other interesting topics.

When did you become interested in architecture, and did the environment you grew up in influence your career choice?

I developed an interest in my future profession from an early age. I was good at drawing and drafting in school and was considered an outstanding student. My teacher noticed my talent for drafting and recommended that I attend classes at the “Pioneers’ Palace,” where I joined various clubs, including an architecture group. This group provided me with basic knowledge and deepened my interest in the field, ultimately influencing my career choice. I can say that my drawing and drafting teacher played a significant role in my professional decision.

Tell us about your career path that shaped your life.

I graduated from high school in 1981, and by my final years, I had already decided to become an architect. At that time, the profession was very popular, so due to high competition, I wasn’t admitted on my first attempt. Later, I was accepted into the Polytechnic Institute (now the Georgian Technical University). I was fortunate to be taught by Shota Bostanashvili, a brilliant person and educator who instilled in us a special love and interest in architecture. He always emphasized that architecture is, first and foremost, a creative field, followed by its technical aspects. Creativity is synthetic and encompasses all disciplines, which is why we would spend hours discussing poetry, literature, and painting. I vividly remember that he encouraged us to visit the first exhibition of abstract paintings at the “Blue Gallery” in 1986—something that was prohibited in the Soviet Union at the time. This was his way of awakening a certain impulse in us to view architecture through a creative lens. I believe that it was largely due to him that I remained committed to my profession, as many of my classmates and acquaintances eventually pursued different fields.

After graduating in 1988, I was assigned to the Department of Cultural Heritage Protection, specifically in the adaptation division, which worked on the restoration and reconstruction of historical landmarks, residential buildings, and urban infrastructure. We completed several interesting projects on Bethlehem Street, in Avlabari, and in the Kala district. During this period, I gained valuable experience working with cultural heritage, which continues to influence my work today.

Everything changed in the late 1980s and early 1990s when civil war broke out. One memory from that time is particularly vivid and symbolic for me. We had an aquarium at work, and my colleague and I sneaked into the building to feed the fish, as we could no longer go to work due to the war. When we entered the office, everything was destroyed—dead fish lay on the floor, sandbags were stacked on the windowsill, and the place had turned into a war zone. The scene was surreal.

Since architecture was no longer a priority, many people turned to business. I, too, experimented with different projects, including an exhibition of wax figures with a friend. It gained some success, even in Moscow, where foreign journalists took an interest, leading to an opportunity to showcase our work in Switzerland. This is how I ended up abroad, initially for two months. During that time, I worked on small projects, expanded my professional network, and, after the exhibition, I continued to return to Switzerland for work. Eventually, I secured a work visa and joined an architectural studio there. Although I held a lower-ranking position, the salary was significant compared to Georgia. Professionally, I developed as well—I was introduced to architectural software that was just emerging in the West.

Living in Switzerland, I experienced democratic values and Western culture, which were unfamiliar to Georgia at the time. I remember speaking about women’s rights and feminism upon returning home, only to be met with skepticism.

Later, my contract in Switzerland was not renewed. Although I had the option to stay, I chose to return to Georgia for various reasons. By then, the war had ended, architecture was regaining relevance, and I realized I could continue my career in my home country. I also wanted to start a family. I understood that in a highly competitive foreign environment, I was just another architect (even though no one made me feel that way). In Switzerland, everything was already built and organized, while Georgia was in ruins and needed reconstruction. All these factors led me back home.

In 2005, along with three partners, I founded the architectural and design firm Architects & Co. Our goal was never to work on numerous projects simultaneously. We believe that architecture is an intimate and creative process, requiring deep engagement. I cannot rest unless I have considered every centimeter of a project. Managing five or six projects at once makes it impossible to maintain full control. Therefore, we prioritize quality over quantity, working on both private and public projects while remaining deeply involved in the process.

What does architecture mean to you?

I fully agree with my teacher—architecture is a creative discipline. Many believe that practicality and functionality are key and that aesthetics are secondary. However, I think the most important aspect is the idea; without it, a building is just a shelter. Architecture inherently carries a creative charge. No architect has ever gone down in history solely for well-lit, functional buildings—design and aesthetics have always been crucial. Of course, creative freedom is not always possible; there are constraints, and not every project allows for personal artistic expression. However, every work should convey a certain idea, a central axis around which everything is built.

Which of your projects would you highlight?

I have worked on numerous cultural heritage sites, including the restoration of Aghmashenebeli Avenue. However, one of my most notable projects is the reconstruction of Legvtakhevi, now a major tourist destination. Previously, the area next to the old sulfur baths was paved and filled with cars, and the Legvtakhevi stream was confined to a tunnel. There is now a global trend against reinforcing rivers with concrete—they should be allowed to flow naturally to support the landscape’s development. Initially, the government only planned minor improvements—paving roads, organizing walkways, and enhancing aesthetics. Meanwhile, a major road was being built in the Vere Gorge, which sparked much controversy. I was able to persuade government officials that uncovering the river and creating a tourist center would be a better long-term solution.

What was initially meant to be a six-month project turned into a three-year endeavor, ultimately transforming the area. Now, pedestrian paths replace the asphalt, and you can hear the sounds of the river and birds. Bringing the river back to life completely changed the atmosphere. The response from the local community was overwhelmingly positive—people frequently approached me to share their memories of the area. Apparently, years ago, the river was used for bathing and everyday needs. Through this project, it felt as if the spirit of Old Tbilisi had been revived.

I also want to highlight the “Akhali Nateba” pavilion on Dighomi Highway, which we designed in 2002. Looking back, there are certainly many things I would do differently now—I would use different materials and new technologies. However, I still believe that this project successfully conveys the core idea and inner energy that should define a structure. Its concept is inherently intriguing—a static concrete wall with a freeform roof placed on top, giving the impression of movement, almost like a dance. The columns are tilted, and no lines run parallel to each other. This creates an interesting synthesis of stability and dynamism, almost like an abstract painting. The floor plan clearly shows the main axis, which acts like a backbone, uniting the bridges, ramps, and stairs inside, giving the entire structure a cohesive form.

It is also essential to mention the projects carried out in Svaneti and the reconstruction of Mestia. My “return” to Svaneti was thanks to my friend and Swiss partner, Markus Rottlisberger. While I was in Switzerland, I organized an exhibition showcasing Georgian culture—wine, music, and my architectural works—to introduce foreigners to Georgia and invite them to visit. In 1997, a group of 15 people came to Georgia, among them Markus, who was particularly fascinated by Svaneti. He started seeking investments for various projects, and together we worked on the development of this region. This led to the construction of a large workshop, an outpatient clinic, and agricultural facilities in Mulakhi. During this time, I repurchased my grandfather’s house in Svaneti, which had been under state ownership, and transformed it into a combined living and working space. I also developed professionally, learning about Swiss approaches and new technologies, including bio-toilet installations, waterproofing under slate roofing, and ecological principles.

Later, when the government launched a large-scale restoration project in Svaneti, I became involved. We worked intensively on Mestia’s reconstruction. Of course, mistakes were made, as happens in any project—it’s impossible to avoid them entirely. However, I strived to execute my parts of the project with the utmost precision and adherence to safety standards. At that time, we renovated Soviet-era buildings, which faced some criticism. I consider this criticism unfair because we gave lifeless structures a new purpose. Another debated topic is the statue of Queen Tamar by Vazha Melikishvili—I personally like it a lot, though opinions on it are divided.

My team was also responsible for the reconstruction of the Lanchvali district. Another historical part of Mestia is the Lagami district, which features terraced courtyards—something rare for Svaneti due to its complex terrain. We completed the project design and even won the tender three years ago. However, due to the region’s complexity, construction has yet to begin, despite strong support from both the government and locals. I believe this project is more refined since we had more time to carefully consider each detail, and I hope we can implement it soon.

Recently, we completed the Limbach Laboratory, several residential buildings, and are actively working on various new projects.

How would you evaluate Georgian architecture? What challenges does it face?

I may not be an analyst, but as a practicing architect, I can say that there is a lot of chaos in this field. There are efforts to bring order to this disorder, but much work remains, as we practically lack an urban planning institution. The master plan that was developed is good but requires constant updating. Environmental damage is widespread in every region. Unauthorized constructions, unhealthy materials, and the destruction of landscapes remain major issues.

For example, in France, there is a village with its own official architectural plan and strict regulations. Construction is only allowed using natural materials—stone, slate, and wood. These norms preserve the village’s authentic look, values, and history, making it attractive to tourists. Unfortunately, we are doing the opposite. The situation in Svaneti is dire. In Ushguli, for instance, the site of Queen Tamar’s winter residence contains one surviving tower and a small basilica, while two other towers have collapsed. This complex is the crown jewel of Svaneti. I attempted to restore it, but the bureaucracy within the Cultural Heritage Protection Agency is immense, especially when it comes to historically significant sites. At the same time, a local resident is building a hotel right behind this important structure—one that is entirely out of context, with ornate metal railings and modern infrastructure that disrupts the historical and cultural integrity of the area. I consider this a crime. In residential buildings of two or three stories, the ancient towers are no longer visible, and Svaneti’s unique character is being lost. The state should regulate such unplanned development. This problem isn’t limited to Svaneti—it’s just more noticeable there. In Tbilisi, the same issue exists, but due to the urban chaos, it is less visually obvious.

Lastly, what advice would you give to young architects?

I interact with young professionals frequently. For years, I taught architecture at Ilia State University. The biggest problem is education. Architecture students have only four 45-minute lectures per week, which is far too little. It is impossible to properly convey information, review each sketch, and provide meaningful feedback when there are 30-40 students in a lecture. A single professor cannot give individual attention to so many students, making the education superficial. If someone succeeds, it is due to their own dedication and effort. That’s why I advise young architects to work relentlessly—their goal should not be to become average architects. Instead, they should strive to be strong professionals who create something truly new.

At the same time, it is crucial to awaken an inner drive. As I mentioned before, I was lucky to have a teacher who inspired my creativity. Young architects should seek ways to cultivate this drive, even if their environment is not supportive. They must find that essential element that makes the profession worthwhile. Today, there are countless ways to do so.

Experience has taught me that if you approach any aspect of design carelessly, even a seemingly minor detail, it will inevitably become a problem later. Every project should be thoroughly thought out and analyzed to be executed flawlessly. Once again, I will emphasize that the core idea is the most important element—everything revolves around it. Creativity must be given room to manifest, and every project should be evaluated with an artist’s eye, whenever possible.

Author: Meko Metreveli

Source: homeis.ge

OTHER NEWS

SEE ALL NEWS